Para sa ikaanim na episode ng Young Critics Circle Podcast, pag-uusapan nina John Bengan, Andrea Trinidad, JC Rosete, Ian Harvey Claros, at Christian Jil Benitez ang pitong pelikula mula taong 2022 na nagkamit ng mga nominasyon mula sa YCC: 12 Weeks (dir. Anna Isabelle Matutina), Batsoy (dir. Ronald Espinosa Batallones), Leonor Will Never Die (dir. Martika Ramirez Escobar), Topografia (dir. Gutierrez Mangsakan II), Kapag Wala Nang Mga Alon (dir. Lav Diaz), Bula sa Langit (dir. Sheenly Gener), at Kitty K7 (dir. Joy Aquino).

Category Archives: Uncategorized

The Young Critics Circle Podcast Ep. 2 – Hinggil sa mga Nominado

Bilang paghahanda sa napipintong anunsiyo ng taunang pagkilala sa kahusayan sa pelikula, matutunghayan sa ikalawang episode ng Young Critics Circle Podcast ang talakayan sa mga pelikulang nominado sa sinematograpiya at disenyong biswal, editing, at tunog sa pelikulang taon ng 2020. Titimbangin nina Aristotle Atienza, Emerald Manlapaz, Tito Quiling Jr., at Skilty Labastilla ang kalidad ng gamit at sangkap ng mga elementong pansine sa mga pelikulang He Who is Without Sin ni Jason Paul Laxamana, Death of Nintendo ni Raya Martin, The Boy Foretold by the Stars ni Dolly Dulu, at Kintsugi ni Lawrence Fajardo.

The 30th Annual Circle Citations for Distinguished Achievement in Film for 2019

The Young Critics Circle Film Desk holds the 30th Annual Circle Citations for Distinguished Achievement in Film for 2019.

10 films vied for citations in each of the seven categories: Best First Feature, Best Sound and Aural Orchestration, Best Cinematography and Visual Design, Best Editing, Best Screenplay, Best Performance, and Best Film. See the full list of winners and nominees here.

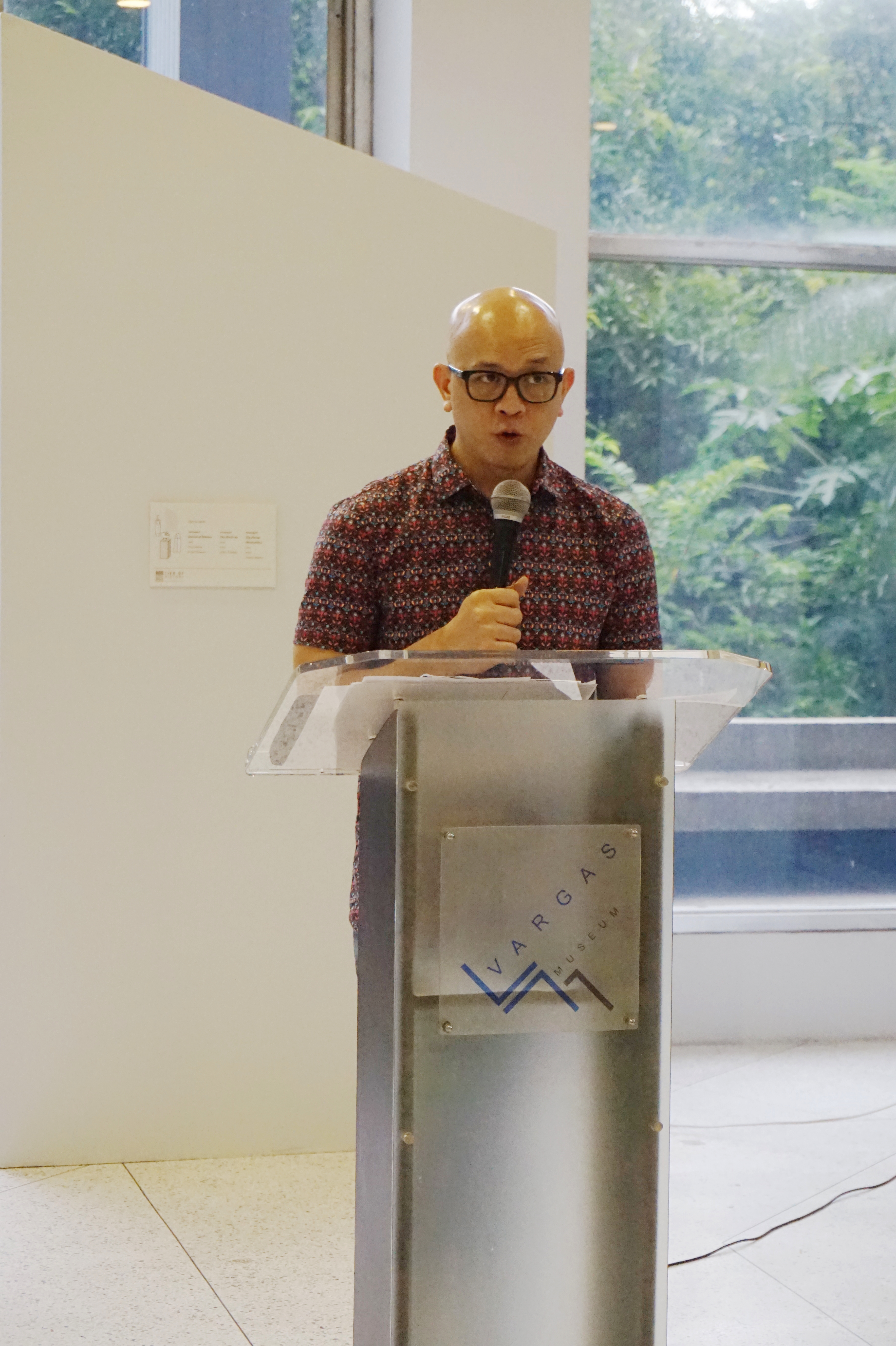

Traditionally held at the Jorge B. Vargas Museum, University of the Philippines-Diliman, the event takes place online for the first time. Dr. Jozon A. Lorenza, a faculty at the Department of Communication, Ateneo de Manila University, delivers the keynote lecture, offering an anthropological critique of Filipino film narratives of the digital.

The 30th Annual Circle Citations catalog is available for download here.

The 30th Annual Circle Citations for Distinguished Achievement in Film for 2019 is supported by the University of the Philippines-Diliman Office for Initiatives in Culture and the Arts (OICA).

Watch the online edition of the 30th Annual Circle Citations, as well as Dr. Lorenzana’s keynote lecture, on the YCC Film Desk Facebook page.

YCC Film Desk Holds Online Edition of 30th Annual Circle Citations

The Young Critics Circle Film Desk invites everyone to its 30th Annual Circle Citations for Distinguished Achievement in Film for 2019.

The ceremony, which is traditionally held at the Jorge B. Vargas Museum, University of the Philippines-Diliman, will be streamed on the Young Critics Circle Facebook page on 30 April 2021 (Friday), 6:00 PM.

Dr. Jozon Lorenzana, assistant professor from the Dept of Communication at the Ateneo de Manila University, is the keynote speaker. Dr. Lorenzana earned a Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology from the University of Western Australia.

This event is supported by the University of the Philippines-Diliman Office for Initiatives in Culture and the Arts.

See the full list of winners and nominees below.

Read the rest of this entry »Love and Liberal Democracy: Alone/Together, Ulan, and Isa Pa, With Feelings

Janus Isaac Nolasco

What does a genre—which trades on kilig, hugot heartaches—have to do with inequality, poverty, human rights, and authoritarianism? If Filipino romance movies barely register on the political scale, one would be hard-pressed to see the genre—generally at least—as anything but politically progressive. But this is misleading. They do not have to literally depict, say, patronage politics, to engage it productively.

There is little explicit political content in Alone/Together, Ulan, and Isa Pa, With Feelings, three films longlisted by the Young Critics Circle for 2019. But they critique hierarchical, patron-client relations; espouse equality; and embrace the liberal democratic values of individualism and self-determination.

Read the rest of this entry »Ang Romantikong Danas ng Dahas sa Realismo

Andrea Anne Trinidad

Realismo ang hulmahang kadalasang nagluluwal ng pelikula sa bansa. Hindi mapasusubaliang hanggang sa kasalukuyan, itong tradisyon pa rin ang madalas katigan ng mga manlilikha sa likod ng mga pelikulang naglalayong paksain ang tila karaniwan nang karanasan ng karahasan na lalong pinasisidhi ng retorikang isinusulong ng kasalukuyang administrasyon kasabay ng aktibo ring pagsasakasangkapan sa mga institusyon at sa lapastangang kalakaran nito. Napagbubuklod halimbawa ang mga pelikulang Alpha: Right to Kill (Brillante Mendoza, 2019), Babae at Baril (Rae Red, 2019), Kalel, 15 (Jun Robles Lana, 2019), at Utopia (Dustin Celestino, 2019) ng iba’t ibang paraan ng pagtuhog ng mga ito sa usapin ng pagbebenta at paggamit ng droga at ng problematikong pag-uugnay ng adiksiyon sa isyu ng kahirapan. Bagaman mistulang realismo ang lenteng ginagamit sa lantarang pag-ukilkil sa napapanahong suliranin, interesanteng natutumbok din ng mga pelikula ang mundo ng romansa sa pagbanat sa hanggahan ng mga establisado na nitong pamantayan.

Read the rest of this entry »A Longer Story of Impunity: A review of A Short History of a Few Bad Things (Keith Deligero, 2018)

Lisa Ito

Keith Deligero’s A Short History of a Few Bad Things (2018), which premiered as part of the Cinema One Originals festival last year, offers several moments that distinguish it from the concurrent line-up of other local murder-mystery thrillers.

The first scenes are enigmatic enough, offering moments that don’t readily align: an underwater scene submerged with whale sharks; a local pawnshop owner is shot in broad daylight, execution-style with a single bullet to the head, at a busy crossing in Cebu City; found, grainy footage of huts burned down during the night, in the year 1998.

The senior investigator tasked to trace the identity of the assassin, an ex-soldier named Felix Tarongoy (Victor Neri), soon finds himself chasing leads that do not also add up, eliding easy answers. Accompanied by rookie colleague Jay Mendoza (Jay Gonzaga) and hounded by the weathered and often exasperated city Chief of Police Ouano (Publio Briones III), Tarongoy finds himself continually outsmarted along the way as witnesses and suspects to the crime are killed in succession. Inexplicably drawn to the widowed Gemma/Maria Calag (Maricel Sombrio) and her farmboy companion Ivan Calag (Kent Divinagracia), Tarongoy defies direct orders and follows a trail that leads back to an exposé and the most unlikely and ironic of encounters.

(Still photo courtesy of Gale Osorio)

(Still photo courtesy of Gale Osorio)

The terse ties that bind each killing to an incident two decades back are revealed here in due time. The film fascinates in its subdued storytelling, cinematography, and haunting soundtracks and music scores that seamlessly connect points in history. Unanswered queries and ominous signs are left for the viewer to complete and decode, while scenes of the chase and its characters foreshadow a longer history of violence that eventually catches up with those who think they have moved on and away.

Among the cast, Neri’s melancholic and Sombrio’s woeful dispositions complement each other well. There is little in terms of overtly theatrical gestures between the two; instead, close up shots during moments of silence best draw out the psychological tension brewing beneath. Conversely, the motley, veering teasingly close to slapstick, mix of Tarongoy’s colleagues and the trio of implicated characters Arturo Binaohan (Reynaldo Santos), Trifon Abueg (Arnel Mardoquio) and Hector (Felicisimo Alingasan) surfaces a sociological taxonomy: conveying in their mimickry of individuals representing the police, the underworld, and charismatic cults a glimpse of the other shadier ties and institutions that bind Philippine society. The screenplay (Paul Grant) which incorporates dialogue in Cebuano, Tagalog, and English is also noteworthy in its exploration of vernaculars.

The strength of the narrative, however, best lies in its ingenious turn towards self-referentiality as it reaches a conclusion. The search for answers boomerangs back to Tarongoy not in the streets of Cebu but in the secluded forests of Masbate island, where he finds himself the subject of scrutiny as he, again, witnesses a moment of final, fiery reckoning. This last stop in the search closes the circle of investigation, while leaving enough gaps for the viewer to fill in any loose ends. One enters a film within a film: and one story begins where the other one ends.

(Still photo courtesy of Gale Osorio)

(Still photo courtesy of Gale Osorio)

This easy-going sense of referentiality is where A Short History of a Few Bad Things (2018) succeeds in resonating with the larger occurrences and longer histories of impunity beyond the work itself. Certainly, the fascination and engagement of Philippine cinema with extra-judicial killing (EJK) narratives is unfortunately still going strong ever since 2016, when the death toll from the drug war under Pres. Duterte started to escalate and was documented through the works of photojournalists, filmmakers, and visual artists. The technologies of visual culture appearing as objects and narrative devices within the film’s storyline —the camera, the phone, and the television in particular —also reference their utility as modes of documentation, evidence, and reenactment.

(Still photo courtesy of Gale Osorio)

(Still photo courtesy of Gale Osorio)

Various intertexts can be read between these and many other local filmic responses to the deaths incurred during the course of both the government’s drug war and counter-insurgency drives. The brutal anti-illegal drug and anti-insurgency campaigns, for instance, have started to intersect in real life through recent developments, such as the issuance of Memorandum Order No. 32 on November 22, 2018 putting the regions of Bicol, Samar, and Negros under heightened army and police presence due to “states of lawlessness”, all leading to a sudden escalation of massacres (especially of peasants), EJKs, political killings, and incidents similar to those portrayed and foreshadowed in the film. That the characters, including Tarongoy, are all eventually implicated in histories of military-instigated incidents ties the narrative closer to contemporary politics.

The real world violence referenced in A Short History of a Few Bad Things, interestingly, underscores such penetration and expansion of impunity out of Manila as a capital to the regions themselves, often hiding in plain sight. The film certainly highlights the tropicality and locality of its setting, further siting this through both language and geography in its shift from urban Cebu to rural Masbate. Connected by water as well as shared histories of trauma as embodied in the tragic figures of Tarongoy and company, these sites of investigation attest to the real atrocity: how state violence is not only national in scope, but also personal, local, and archipelagic in its reach as well.

What kind of redemption is implied in the end? Vigilante vengeance, or justice, whether of the protracted or ironic kind? A sense of ambiguity lingers in the particular trajectory that this proposes. Certainly, killers outside the filmic realm roam still freely up to now. But the film issues an ample warning to all those concerned: the bells will toll not only for those you felled, but also for thee.

Strumming the Void: Notes on Dwein Ruedas Baltazar’s Oda sa Wala (2018)

Christian Tablazon

At its heart, the title Oda sa Wala already announces a perverse, desiring subject enfolded in a long and fraught enactment of apostrophe. The film opens with what is probably one of the most arresting and thoughtful first scenes in recent cinema: a lingering take of winged insects drawn in a graceful flurry to the ceiling light while an old, melancholic Chinese song (what initially seems a non-diegetic tune) plays in the background. The shot is later revealed to be Sonya’s POV, a woman in her 40s lying wide awake and alone in bed, immersed in the same song that turns out to be playing through her earphones from a Walkman. The door creaks and a disembodied hand slips into the crack to switch off the light in the room. Sonya waits for a while in the dark before getting up to turn the ceiling lamp back on. She returns to bed and resumes listening to the song, but the player gets jammed right away. She opens her Walkman and finds the tape spilled out of its cassette. The drone of bugs outside accompanies the silence in the house. The seeming ghost, we will later realize, is Sonya’s father, just lodged wordlessly in the next room.

The father has been turned into a phantom sign, reduced into a fragment without context, an incomplete figure without speech, absent and present at once in the same house with her. Sonya is alone with and in spite of him, throughout the solitary passage of night, just as long as the nights that came before. Besides her winged and incidental companions, she is also kept company by a conjured voice that is only as spectral, that of a foreign woman, now probably dead, singing in another language, recorded from a different place and time, a facsimile of a human voice crooning from an obsolete cassette tape, a serenade long gone returning from the other side, mechanically invoked through a handheld apparatus. It is also a disembodied voice, whose words Sonya protractedly hums and mouths in this moment of strange communion with insects and ghosts.

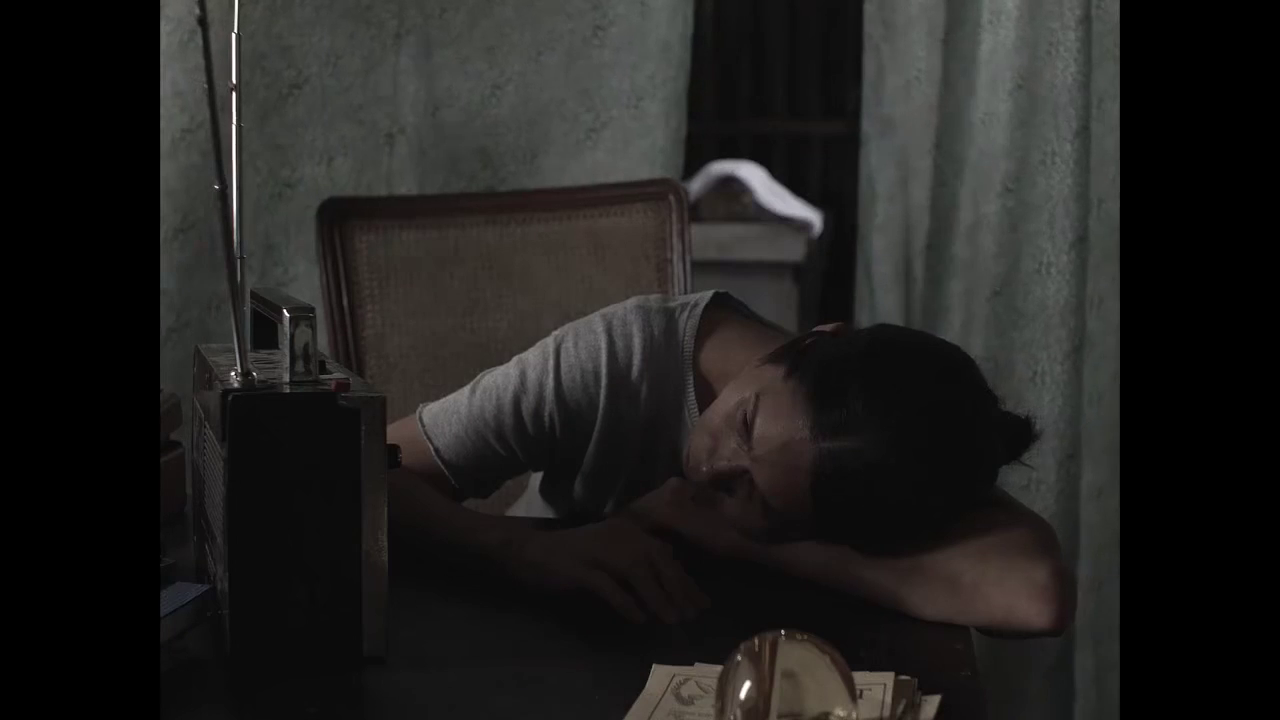

(Screengrab from Oda sa Wala‘s trailer)

(Screengrab from Oda sa Wala‘s trailer)

The numinous beauty in this commonplace and transient moment that she witnesses amid her desolation, the music drifting from a distant time and place into an almost ethereal sight of these fascinating alate forms—the winged iteration of their kind—these ephemeral lives, and their mysterious attraction to light for which even science still could not fully account…. With this opening scene, the silent and ambiguous gaps and gestures that protract the visible, Sonya’s conscious reality, and the film’s narrative, not only build a decisive atmosphere within which to unfold this strange and excruciating meditation on loneliness and acquaint us with the lyric and oblique tendencies of Baltazar’s evocations, but also situates the cardinal motifs of haunting and return, strange unsuspected visits, artifact and disintegration, darkness and light, disembodiment and embodiment and surrogate incarnations, and the fleeting little joys and glimpses of numen that seep through the cracks of ennui and terror.

Caught between dead mothers and men who consistently fail her, she feels invisible and unwanted, a subject on the verge of being neutered and extinct at once: Sonya, a soltera and no longer young, lone and all-around mortician at her family-owned funeral home of over 50 years, struggling to keep at bay the drawing impoundment of their property by a ruthless loan shark who is perennially sapping their resources. She is trapped with her languishing father in the soulless, day-to-day humdrum in their large, decrepit house, and their lives are almost determined by the castrating loss of the wife and mother in the wake of her passing. A gloomy, womblike and pluvial atmosphere looms and persists about the house. The dead clock, the phased out media, the sheer gesture of playing same old song, on loop, over and over sums up limboid inhabitation suspended in time. The radio that, despite Sonya’s repeated attempts, could not process any signal, amplifies the insularity of their lives in their silent and cavernous home. Marietta Subong’s deft and visceral portrayal of Sonya steadily unravels a brutal and incommensurable solitude, and renders, with utmost empathy and dignity, how the perverse can sometimes shed light on our humanity, how the perverse itself is the mark of humanity, the individual human sign she carries.

(Screengrab from Oda sa Wala‘s trailer)

(Screengrab from Oda sa Wala‘s trailer)

Several times in the film, Sonya would be listening to the same song in the beginning, a quaint and bittersweet 1950s rendition of “Jasmine Flower”, a Chinese folk song, which actually bookends the film. Possibly, for Sonya, it is a tender remnant from happier days, a reminder perhaps of a Chinese-Filipino mother or from when she was younger and alive, or an intimate souvenir between her parents conceived when they were young passionate lovers, a hand-me-down tune she plays over and over, frequently spoiled by the stubborn cassette tape getting stuck and tangled, a flimsy bequest now literally unravelling into unusability. The lush invocations of this song starkly contrasts with the cauterized dimension of Sonya’s life, and most so when she hums and mouths her slurred version of the Mandarin lines while caught in her reverie, her eyes cast distantly upon the emptiness before her.

Amid the Orientalia of conflated Chinese and Japanese ornaments in her study, we see an old, yellowed poster advertisement that says, “See CHINA by PLANE”. The slogan compounds the song’s signification as an impossible place, an ever-elsewhere for which the protagonist longs. The narrative thus positions the song as the last bastion of her sensual habitude, alongside the few other little retreats she affords herself that sustain her person: the shabby piano the loan shark takes away, her mother’s photograph, the prospect of being able to one day travel to China as hinted by the poster, smoking cigarettes, buying her own birthday cake and the blissful dancing that ensues over lunch, and, of course, her brief encounters with Elmer, the young taho vendor whom she fancies and anticipates every morning.

Sonya’s retreat from her seemingly embalmed state takes a more aggressive turn in the form of a mysterious corpse, a woman most likely around the same age as her dead mother, that finds its way into their home one very late evening. The corpse in itself is ambiguous in its being n/either subject n/or object, an uncanny figure that blurs the distinction between self and other, setting up a rigodon of ghostly functions: as itself, as a set of analogs, as surrogate, as Sonya’s alter ego, and as a portent to her fate.

The dead turns out auspicious, and Sonya eventually decides restitute her mother through the surrogate corpse, fecundating their household and the relationship between daughter and father. In one particular bedtime scene, the Chinese song she obsessively listens to in various instances in the film presently functions as the interface and buffer between two simulations by Sonya: the memory of her dead mother and its embodiment in the surrogate corpse of this unknown woman.

(Screengrab from Oda sa Wala‘s trailer)

(Screengrab from Oda sa Wala‘s trailer)

The premise of Oda sa Wala easily conjures a similar trope in García Márquez: the arrival of a strange and exquisite corpse—The Handsomest Drowned Man in the World—in the lives of the inhabitants of a small coastal village forever alters the people and brings forth an unprecedented Spring and flowering that their village could never have otherwise imagined. However, while the corpse in Oda sa Wala catalyzes a chain of auspicious and bizaare events that will eventually fulfill Sonya’s fate, one realizes that the role the mysterious dead woman plays here is a brief distraction, a reprieve, allowing Sonya and her father a momentary relese from the limboid tautology of their day-to-day existence, before the Void fully encroaches upon them and the corpse finally reveals itself to be the Void, before the world swiftly and compeletely falls away to evince a new order. “One curious property of the cuttlefish is that, once dead, its body begins to glow,” Srikanth Reddy writes in one of his poems. “This mild phosphorescence reaches its greatest intensity a few days after death, then ebbs away as the body decays. You can read by this light.” The last sentence completes the full circle that pertains to a psalm being unfolded in the poem, the psalm that is itself the very poem we are consuming in the ebbing light of a carcass. This “mild phosphorescence”, this seeming miracle of luminosity, that momentary grace in spite of and resulting from the process of physical corruption, is a most fitting analogy to the workings of the perverse in Oda sa Wala and Sonya’s relationship with the Void.

Apart from the recurring Chinese song, “Jasmine Flower”, the motif of efflorescence also finds multiple iterations in the tiny details throughout the film: flowers for the dead, Sonya’s floral pillows and sheets, the spring flowers painted on her bedhead and the framed image of a flower hanging above it, the floral pattern on a wall clock, and her floral-printed blouse when Sonya has decided to doll up for Elmer, the young man she likes, her first and only clothing that bears noticeable color and design within a series of drab and printless clothes she wears in the film. This floral motif persists in the narrative, and Baltazar potently deploys the trope of nuptial spring against the soltera’s abject and barren connotations, mining the poignant and morbid irony of such juxtaposition. “Before you got here, I thought… maybe it would be better if I just disappeared,” Sonya tells the auspicious corpse she has just done up, and whom she addresses as her deceased mother, pretending that the latter has finally returned to somehow deliver Sonya from the curse of her solitude. Dressed in newly bought clothes and crowned with a wreath of flowers, the dead woman transforms into Sonya’s spring goddess and her very own Flower Girl. In the traditional symbolism of the wedding procession, the flower girl leads the bride forward, from childhood to adulthood and from innocence to her roles as both wife and mother.

The realm of social reason and cultural order are sustained and plotted by the rhythm of habits and negotiations in the story: the consumption of media; the business of minding the dead; service rates and other regulations of value; keeping time: her age, her birthday, the closing hours at work, meals, mornings waiting for Elmer, and the loan shark scheduled visits; the fuss over private property and title; the obligation of paying the debt; the old grand piano being sequestered as a partial mode of payment, and the assigned value of things, commodities and mementos alike; paying the jeepney fare; the pressure of relationships and civil status; familial relations; or the admissible truth of photographs.

The void is neither sheer absence nor wretched abstraction; its nothingness possesses a ruthless and irrevocable materiality that alters and impinges upon this world of bodies, in the same acoustic logic that the hollow against which the strings are stretched amplifies the trill, and hence a song, however sad or frightening. Sonya strums the Void into emerging its voice, the voice of the Other, and to which she would ardently answer, devoting herself fervidly to fill the emptiness, in the process becoming the very plug in the hole of the Other. In her encounter with the frightening Void, she willfully turns into the transitive object that completes this Otherness: the subject herself stopples Nothing precisely by inhabiting it.

The dark womb slowly retracts the world, engulfs it. Her absence has taken over father and daughter, a palpable void that encroaches upon the house and gradually frays the waking lives of its occupants. Sonya permits her return as a different corpse, and the dead, just like absence, is never passive. Her body discolors and distends. She decays and the foul smell pervades the house. Her absence-presence alters place and the relations and bodies within it, the Void taking on a material shape through the very characters it subsumes, the same figures that carry it out in turn. The otherness that is Nothing encroaches upon Sonya’s daily existence and gradually frays social reason, until she finally turns herself into the object for the jouissance of this Other—a gradual descent, or transmutation, that the film patiently charts with keen and excruciating sensitivity, along with the sounds of inarticulable terrors and longings.

The photograph as document loses its indexical power as the woman’s corpse has come to nullify and supersede it as the more palpable icon of the dead mother. The corpse exceeds the business deal when it stops being just what it is, its keeper Sonya refusing attempts to claim the body, as the dead woman has now been espoused into their household. The flowers are mere simulacra and the real ones have ceased being plants and become no more than retailed commodities. A bag of cash becomes a bag of newspaper scraps. The old wall clock looms dead, the cassette tape unravels, and the wheezing radio goes mute, and crackles. The sputtering engine of the funeral hearse fails and the two passengers are stuck on the side of the road stretching along the looming forest. Sonya witnesses the very embodied apparition of the old woman, alive and apotheosized into a naked earth god, an ancient figure subsuming the intertwined deifications of nature, fertility, creation, and destruction. It is night all of a sudden, and Sonya, under the full moon, follows her mother into the depths of the forest. She plods through the wilderness, to the sonorous, celestial aria of a woman’s voice, toward her own clearing, her own banwa, to go phantom into the ever elsewhere that will finally fulfill her. When both women, now deep in the woods, finally inhabit the same frame, the dreamy and melancholic trill of notes shared by both the music in the final scene and the flourish of strings in the old Chinese song merge as well into the same stream, right before the moment cuts to black and closing credits. Ablution or dead end, primal regression or death, transcendence or madness, rebirth or extinction. In the end, in the last gesture of an open-ended reprieve, she may well believe, and insist, that the void has sung back after all.

The 29th Annual Circle Citations for Distinguished Achievement in Film for 2018

The Young Critics Circle Film Desk invites everyone to its 29th Annual Circle Citations for Distinguished Achievement in Film for 2019.

The ceremony will be held on 16 August 2019 (Friday), 3:00 PM at the Jorge B. Vargas Museum, University of the Philippines-Diliman.

Dr. Joseph Pális, assistant professor at the Department of Geography of the University of the Philippines Diliman, is the keynote speaker. Dr. Pális is also an affiliate faculty in the Center for International Studies in the same university.

This event is open to the public and is supported by the University of the Philippines-Diliman Office for Initiatives in Culture and the Arts.

BEST FILM

Sa Palad ng Dantaong Kulang, directed and produced by Jewel Maranan

BEST PERFORMANCE

Nadine Lustre, Never Not Love You

BEST SCREENPLAY

Masla A Papanok (Gutierrez Mangansakan II)

BEST ACHIEVEMENT IN EDITING

Call Her Ganda (Victoria Chalk)

BEST ACHIEVEMENT IN CINEMATOGRAPHY AND VISUAL DESIGN

Sa Palad ng Dantaong Kulang (cinematography: Jewel Maranan)

BEST ACHIEVEMENT IN SOUND AND AURAL ORCHESTRATION

Never Not Love You (music: Len Calvo; sound design: Jason Conanan and Kat Salinas)

BEST FIRST FEATURE

Mamang (Denise O’Hara)

Mamu; And a Mother Too (Rod Singh)

Ang Pangarap Kong Holdap (Marius Talampas)

The 28th Annual Circle Citations for Distinguished Achievement in Film for 2017

The Young Critics Circle Film Desk held its 28th Annual Circle Citations for Distinguished Achievement in Film for 2017 last 16 August 2018 (Thursday), 4:00 PM at the Jorge B. Vargas Museum, University of the Philippines-Diliman.

Dr. Jazmin B. Llana, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, De La Salle University-Manila, was the keynote speaker. Dean Llana is also Chair of the Research TWG of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts and the Vice President of Performance Studies international (PSi).

This event is supported by the University of the Philippines-Diliman Office for Initiatives in Culture and the Arts.

To get a copy of the citations catalogue, please click on this link: YCC complete 2018 081518

Photos

(All photos taken by Lea Marie Diño of Vargas Museum)

The trophies.

YCC members Skilty Labastilla and Em Flaviano host the ceremony.

YCC chairperson Lisa Ito-Tapang delivers her opening message and introduces the keynote speaker, Dr. Jazmin Llana of the De La Salle University-Manila.

Dr. Jazmin Llana delivers her keynote speech.

Skilty Labastilla reads the citations for Best First Feature.

Best First Feature award recipients Thop Nazareno (Kiko Boksingero), Rae Red (co-director with Fatrick Tabada, Si Chedeng at Si Apple), and James Robin Mayo (The Chanters) pose with their trophies.

James Robin Mayo gives a speech.

Rae Red gives a speech.

Thop Nazareno gives a speech.

YCC member Christian Benitez reads the citations for Best Achievement in Cinematography and Visual Design.

Elora Espanto and Joseph Israel Laban representing Marielle Hizon and TM Malones, respectively, pose with Benitez with Hizon’s and Malones’ trophies for Best Achievement in Cinematography and Visual Design for Baconaua.

Shireen Seno (co-editor with John Torres) poses with their trophy for Best Achievement in Editing for Nervous Translation.

Seno delivers a speech.

YCC member Aris Atienza reads the citations for Best Achievement in Sound and Aural Orchestration.

Mikko Quizon (sound design) and Itos Ledesma (music), awardees of Best Achievement in Sound and Aural Orchestration for Nervous Translation, pose with Atienza.

Quizon gives a speech.

Ledesma gives a speech.

Ledesma performs “For a Beautiful Human Life” from Nervous Translation.

YCC member Jaime Salazar reads the citations for Best Screenplay.

John Paul Bedia and Andrian Legaspi pose with their trophies for Best Screenplay for The Chanters.

Legaspi gives a speech.

Bedia gives a speech.

YCC member J Pilapil Jacobo reads the citations for Best Performance.

Anthony Falcon poses with his trophy for Best Performance as Amanda in Mga Gabing Kasinghaba ng Hair Ko.

Falcon gives a speech.

YCC chairperson Lisa Ito-Tapang reads the citations for Best Film of 2017.

Joseph Israel Laban with his trophy for Best Film for Baconaua, with Ito-Tapang.

Laban gives a speech.

Incoming YCC chairperson Em Flaviano introduces the current membership of YCC and welcomes new YCC member, Tito R. Quiling Jr.

The awardees and nominees pose with the YCC.

After the program, Falcon chats with Jacobo.

(L-R) Skilty Labastilla, J Pilapil Jacobo, Anthony Falcon, Tessa Guazon, and Patrick Flores.